If you’ve worked with Internet of Things (IoT) devices, you’ve probably come MQTT. Short for Message Queuing Telemetry Transport, MQTT is one of the most widely used messaging protocols for connected devices. It’s lightweight, efficient, simple to implement, and designed specifically for environments where bandwidth is limited and reliability matters.

In this post, we’ll dive into MQTT, why it was created, and how it works under the hood, including its topic system, quality-of-service levels, retained messages, Last Will & Testament features, and important additions introduced in MQTT 5.

I cover much of the same material in this post as I did in this video

Table of Contents

A Brief History of MQTT

MQTT’s roots go back to 1999, when Andy Stanford-Clark (IBM) and Arlen Nipper (Eurotech Inc.) were tasked with building an efficient way for battery-powered sensors on remote oil pipelines to send telemetry through satellite networks. Satellite bandwidth of the ’90s was extremely limited, and sending even modestly sized messages was expensive.

To solve this, Stanford-Clark and Nipper designed a protocol that emphasized:

- Minimal packet size

- Persistent, low-overhead TCP/IP connections

- A simple publish/subscribe model

- Reliable delivery options for unreliable networks

At the time, IBM’s enterprise messaging tools were branded under the MQSeries name (“Message Queue”), and while MQTT doesn’t actually implement message queues, IBM added the “MQ” prefix for brand consistency. Thus, MQ Telemetry Transport was born. Fast forward to 2013, and IBM transferred maintenance of the protocol to the Organization for the Advancement of Structured Information Standards (OASIS). OASIS has since standardized and maintained MQTT under the full name Message Queuing Telemetry Transport. Today, MQTT is used in many IoT networks, from home automation platforms like Home Assistant and OpenHAB to massive industrial systems, agriculture sensors, vehicle telematics, and factory automation.

The Pub/Sub Model

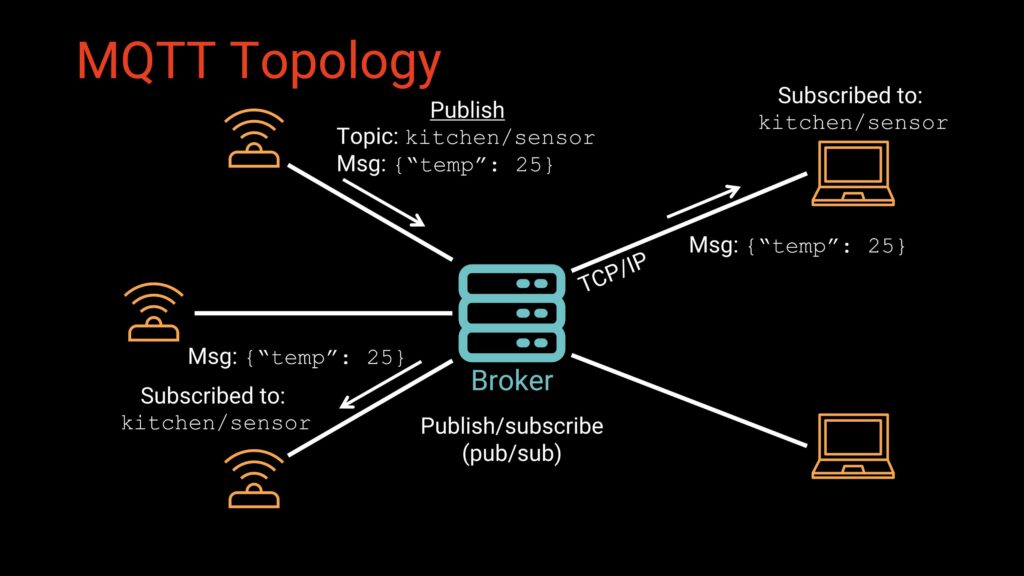

At its core, MQTT uses a publish/subscribe architecture, often shortened to pub/sub. If you’re used to request/response patterns like HTTP, this may feel unusual at first. Instead of devices directly messaging each other, communication flows through a central broker. The model relies on three main components: the broker, clients, and topics.

The broker is the central component of any MQTT network. It runs as a service (either on a local machine or a cloud server) and is responsible for managing all communication between devices. The broker accepts inbound TCP/IP connections from clients, authenticates and tracks those clients, receives any messages they publish, and then routes those messages to the appropriate subscribers. It does not process or interpret payloads, but rather, it ensures that data flows efficiently and reliably through the system. Commonly used brokers include Mosquitto, EMQX, HiveMQ, and VerneMQ.

MQTT clients are simply devices or applications capable of connecting to the broker over a network. These can range from small microcontrollers such as the ESP32, STM32, or RP2040 to embedded Linux boards like the Raspberry Pi, as well as desktop computers, mobile applications, and cloud-based services. Once connected, a client may publish data, subscribe to specific topics, or do both, depending on its purpose. Because the protocol is lightweight and flexible, virtually any network-enabled device can act as an MQTT client.

The way MQTT routes data is through topics, which are UTF-8 strings that function like folder paths or chat room channels. A topic such as home/kitchen/temperature describes the kind of information being exchanged, allowing clients to publish data to that channel or subscribe to receive updates from it. Unlike traditional request/response networking, MQTT’s publish/subscribe system means that publishers do not need to know who receives their data, and subscribers do not need to know where the data originates. This decoupling allows multiple subscribers to receive the same information instantly, makes it easy to add or remove devices without modifying system logic, and provides strong resilience in networks where connectivity can be intermittent. We’ll examine topic syntax in greater detail in the next section.

MQTT Topics

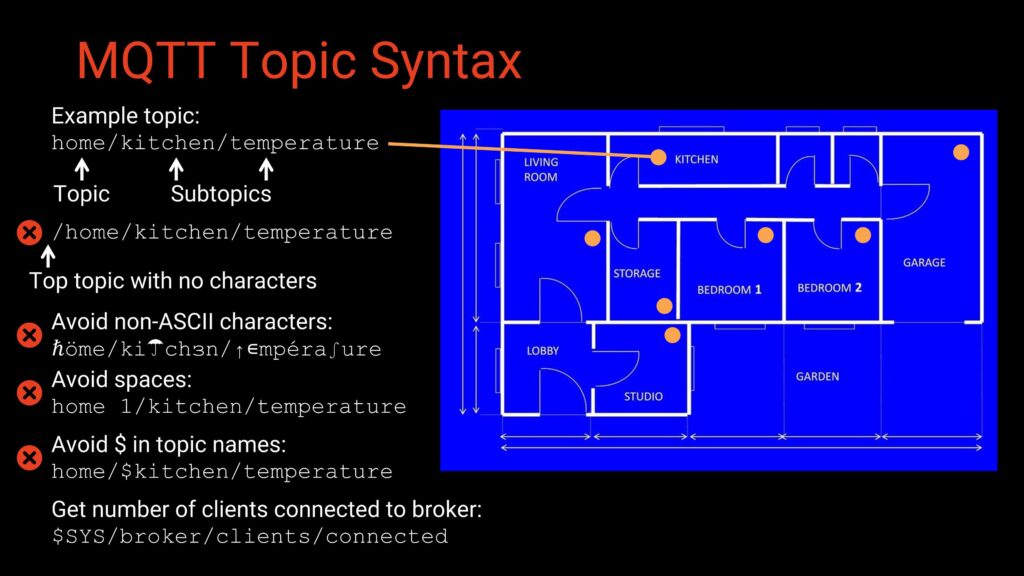

Messages in MQTT are not addressed using IP addresses or device IDs. Instead, they are routed using topics. A topic is a UTF-8 string such as:

home/kitchen/temperatureYou can think of topics like folder paths or chat room channels. Clients can publish to a topic or subscribe to it. When any client publishes to a topic, the broker delivers that message to all subscribers of that topic. As a result, publishers do not need to know anything about subscribers, multiple subscribers can receive the same data simultaneously, and adding or removing devices does not change any device-to-device logic

This setup works extremely well in networks with intermittent connectivity.

MQTT topics are hierarchical, with each level separated by a /. For example:

home/kitchen/temperature

home/livingroom/humidity

Here are some recommended guidelines for topic naming:

- Technically any UTF-8 characters are allowed, but stick to ASCII for consistency.

- Avoid spaces; not all clients handle them well.

- Avoid leading slashes—they create an empty root topic.

- Avoid topic names beginning with $, which are usually reserved for broker system info (e.g., $SYS).

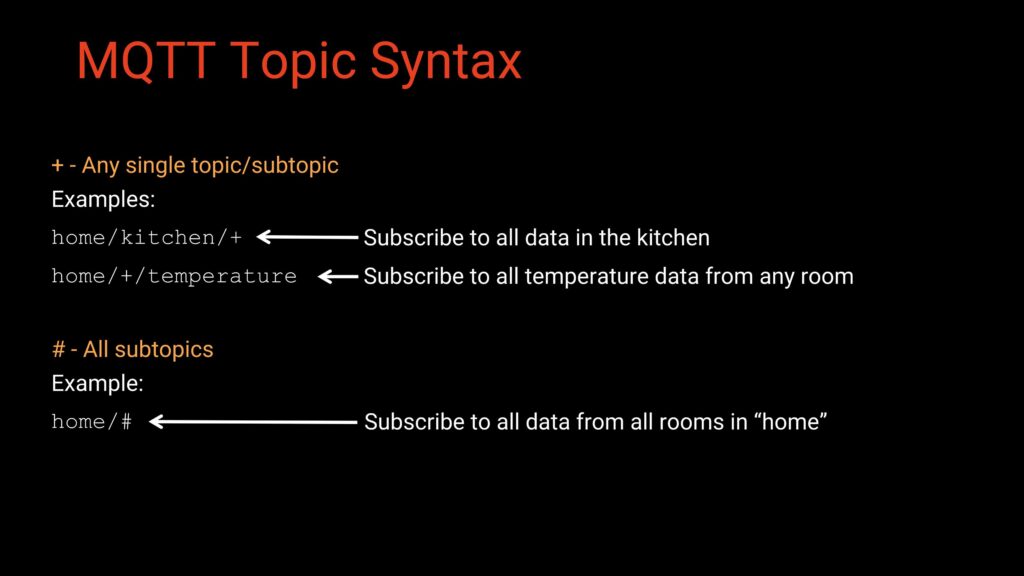

Note that MQTT provides two wildcard options for subscribing: single-level wildcard (+) and multi-level wildcard (#).

Storage Options

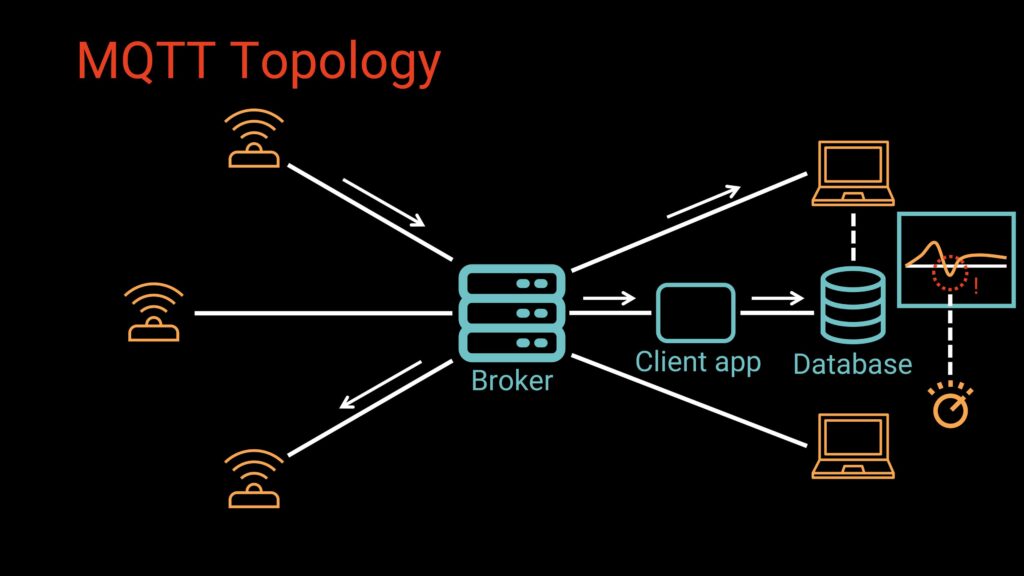

Note that (with some exceptions), the brokers do not store data. They are designed to be lightweight routers, not databases. However, applications often want historical sensor data (e.g. displaying temperature data over time on a dashboard). This is often accomplished using three tools (either configured separately or as part of a complete IoT package, such as ThingsBoard):

- An app (often called a “bridge”) subscribes to selected topics

- It stores messages in a database (MySQL, PostgreSQL, InfluxDB, etc.)

- Dashboards, analytics tools, or ML models consume that stored data

Client IDs

Every client must identify itself to the broker using a Client ID, up to 256 UTF-8 characters. Most developers use simple ASCII:

kitchentemp_A7F391

robot_23

weatherstation-livingroomUniqueness matters: if two clients connect with the same Client ID, the broker may disconnect the older one. You’ll also come across patterns where part of the device’s MAC address is appended to the sensor’s name to generate the client ID.

Quality of Service (QoS)

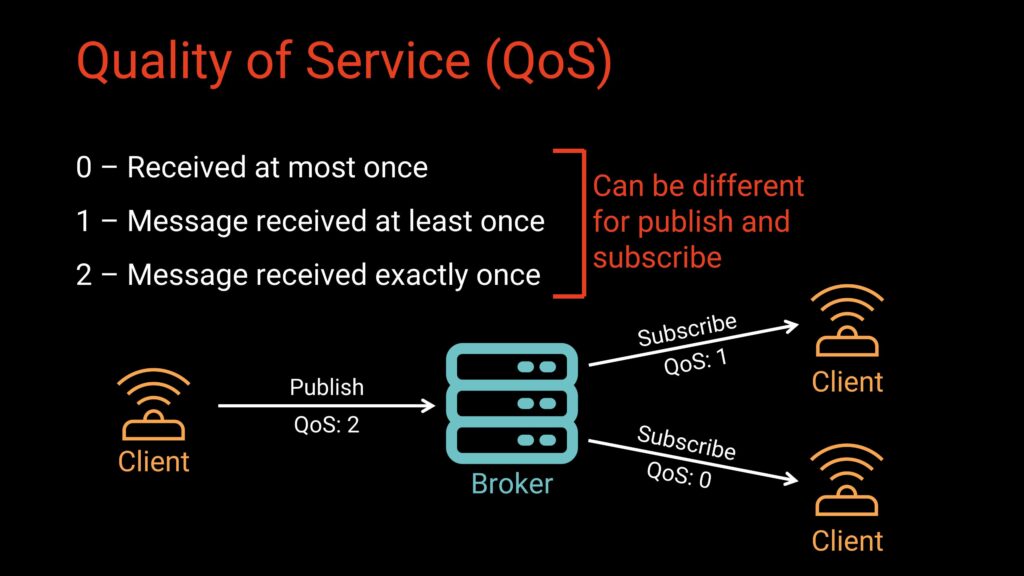

MQTT defines three Quality of Service levels that determine how messages move between clients and the broker, allowing developers to balance reliability, performance, and network overhead. Let’s look at the three QoS levels:

QoS 0, often summarized as “at most once,” sends each message a single time without requiring any acknowledgment from the receiver. Because the sender never retries, messages may be lost if the connection drops, but the overhead is minimal. This makes QoS 0 well suited for high-frequency sensor data or noncritical updates where occasional loss is acceptable.

QoS 1, or “at least once,” adds a reliability layer by requiring the receiver to acknowledge each message. If the sender does not receive an acknowledgment within a certain timeframe, it retransmits the message until confirmation arrives. While this guarantees that the message will be delivered, it can also lead to duplicates, so it works best for messages that are important but idempotent—such as telemetry uploads or commands like “turn the light on,” where receiving the same message twice does no harm.

QoS 2 provides the strongest guarantee, ensuring a message is delivered exactly once through a more complex four-step handshake between sender and receiver. Because this process adds significant overhead and can slow down communication, QoS 2 is typically reserved for critical commands or data where duplicates could cause problems, such as precise actuator instructions or sensitive industrial control signals.

MQTT also supports persistent sessions, which allow brokers to queue QoS 1 and QoS 2 messages for clients that temporarily disconnect. When those clients reconnect using the same session, the broker delivers any pending messages, making the system more resilient in environments with unstable connectivity.

It’s also important to note that MQTT handles QoS levels independently for publishing and subscribing, which means the QoS a client uses to send a message may not be the same QoS another client uses to receive it. The publish QoS controls how reliably the message reaches the broker, while the subscribe QoS determines how the broker delivers that message to each subscriber. As a result, different clients can receive the same message at different levels of reliability based on their own requirements. For example, a sensor might publish temperature readings at QoS 0 to keep overhead low, while a monitoring dashboard subscribes at QoS 1 to ensure it receives every update, and a data logger subscribes at QoS 2 to guarantee an exact, duplicate-free record. This flexibility allows each device in an MQTT system to optimize performance, reliability, and bandwidth according to its specific role.

Retained Messages

MQTT includes a useful feature called retained messages, which allows the broker to store the most recent message for a given topic. When a client publishes a message with the retain flag set, the broker saves it instead of discarding it after delivery. Any new client that later subscribes to that topic immediately receives the retained message, giving it the latest known value without waiting for the publishing device to send an update. This behavior is particularly helpful in systems where updates are infrequent or where new devices need an instant snapshot of the current state.

Retained messages work well for things like the latest temperature reading, the on/off state of a device, configuration parameters, or general system status. It’s important to note that brokers store only one retained message per topic, and they do not add timestamps automatically. If your application needs to know when the value was last updated, the publishing client must include that information in the payload itself.

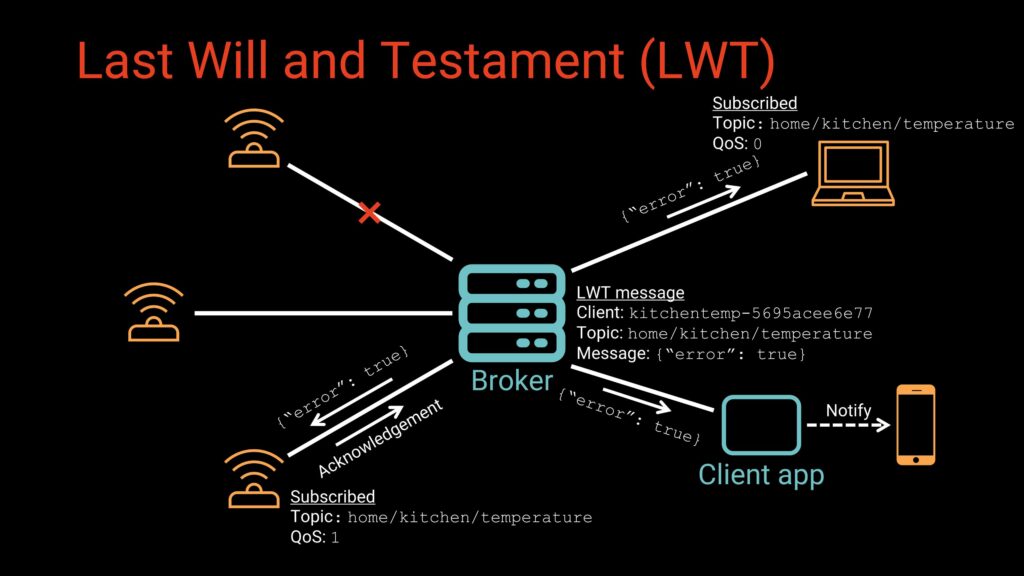

Last Will and Testament (LWT)

MQTT provides a built-in mechanism for detecting unexpected client failures through what’s called a Last Will and Testament (LWT) message. When a client connects to the broker, it can specify a topic, payload, QoS level, and optional retain flag that make up its LWT. The broker holds this message in reserve and does nothing with it as long as the client disconnects normally. However, if the broker detects an abnormal disconnect (whether due to a crash, network interruption, or sudden power loss) it automatically publishes the LWT message on the client’s behalf.

This feature is especially useful for monitoring the health and connectivity of IoT devices. An LWT message can signal that a sensor has gone offline, trigger alerts for administrators, or activate automated recovery actions such as switching control to a backup device. By providing a reliable way to detect failures without requiring constant polling, the LWT helps maintain robustness in networks where connectivity may be unpredictable or devices operate in harsh environments.

Common Format Types

MQTT intentionally avoids prescribing a payload format. You can choose whatever fits your system. However, you’ll often come across a number of common formats. Let’s look at a few of them:

- Plain text: Single values (e.g.

23.1), instructions (e.g.ON), or comma-separated value lists (e.g.23,45,18) are common plain text payloads. - JSON: JSON is very common in IoT because it’s human-readable and supports structured data. For example:

{ "temp": 23.1, "humidity": 41 } - XML: Less common but still seen in enterprise systems.

- Binary: Useful for payloads that contain images, audio, sensor streams, or over-the-air (OTA) firmware updates.

MQTT 5: New Features

MQTT v3.1.1 (from 2014) is still widely used, but MQTT 5, released in 2019, adds significant improvements. Let’s go over some of the notable additions:

- Message and Session Expiry: Messages can be dropped after a configurable timeout. This can be helpful in preventing outdated QoS 1 os 2 messages from lingering.

- User Properties: Custom key-value pairs can be added to message headers, enabling metadata handling and custom broker behaviors.

- Shared Subscriptions: Enables load balancing. This syntax adds a share keyword and groupname. For example:

$share/groupname/home/kitchen/temperature. Only one client in the group receives each message, which is useful for high-volume processing pipelines. - Improved Request/Response Patterns: Allows a client to issue a request on one topic and receive a direct, uniquely identifiable (based on the newly added Correlation Data field) reply on another without relying on custom conventions or ad-hoc topic schemes.

- Better Error Reporting and Scalability Features: This includes reason codes, enhanced authentication, and more control over message limits.

If you want to dive deeper, HiveMQ has a fantastic two-part series that covers the additional features found in MQTT 5 (part 1, part 2).

Security Practices

Because MQTT transmits all data (including usernames and passwords) in plaintext by default, a secure deployment starts with enabling authentication and encryption. Most brokers allow you to assign usernames and passwords to clients, but this alone is not enough unless the connection is protected. Implementing TLS (Transport Layer Security) ensures that all MQTT traffic is encrypted, preventing attackers from sniffing or tampering with messages in transit. In production environments, it’s best to use certificates signed by a trusted authority, such as those provided by Let’s Encrypt. For even stronger identity verification, some deployments use mutual TLS, which requires both the broker and the client to present valid certificates before communication is allowed.

Beyond encryption, robust authorization and operational controls play an important role in keeping an MQTT system secure. Configuring Access Control Lists (ACLs) lets you define exactly which clients can publish or subscribe to which topics, limiting the damage a compromised device can cause. Implementing message rate and size limits helps mitigate denial-of-service attacks by preventing clients from flooding the broker with excessive traffic. And finally, keeping broker software, client libraries, and device firmware up to date reduces vulnerability to known exploits. When combined, these practices create a secure foundation that allows MQTT to operate safely even in large, distributed IoT environments.

Conclusion

MQTT has earned its reputation as a lightweight yet powerful protocol for IoT and distributed systems. Its simplicity, flexibility, and scalability make it a natural choice in areas like home automation, industrial monitoring, robotics, smart agriculture, and many more. The publish/subscribe architecture decouples devices, making systems easier to design, expand, and maintain. Features like QoS, retained messages, and LWT give developers powerful tools to build reliable solutions, even in unreliable networks. If you’re planning an IoT project, MQTT is worth exploring. Combined with a modern broker and proper security configuration, it provides a robust foundation for real-time, distributed communication across thousands (or even millions) of devices.

If you would like to see MQTT in action, check out my IoT Firmware Development with ESP32 and ESP-IDF course. In the course, we cover the basics of ESP-IDF, reading from sensors, connecting to the internet via WiFi, posting data via HTTP REST calls, securing connections with TLS, and interacting with MQTT brokers.